The Road to Providence

by Robert Derie – 2015

Around 1994 David Mitchell of Oneiros Books approached Alan Moore to contribute a story for The Starry Wisdom: A Tribute to H. P. Lovecraft (1995). Moore’s initial idea was for a novel called Yuggoth Cultures, which would consist of a series of short text pieces, prose-poems, and vignettes—“cuttings, spores if you like”—from Lovecraft’s sonnet-cycle Fungi from Yuggoth. Unfortunately, before Moore could complete more than six or seven pieces more than half of the only copies were lost in a cab in London, and the novel was abandoned.One substantial story, “The Courtyard,” appeared in the original Starry Wisdom anthology, which came out in 1995.

Two other text pieces, “Zaman’s Hill” and “Recognition,” were published in Dust: A Creation Books Reader (1995). These text pieces were included in the updated 2003 edition of The Starry Wisdom, which states that they are from Moore’s Yuggoth Cultures listed as “forthcoming.”

Moore had first read Lovecraft while in grammar school, but rarely if ever directly referenced his work prior to the Starry Wisdom anthology—no doubt because he never really ventured into the realm of horror, after his seminal run on Swamp Thing. However, the appeal of Lovecraft’s mythology, or at least its availability in the public domain, was enough for Moore to draw on it in his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comics, most notably in the back-up prose story “Alan Quartermain and the Sundered Veil” in book one (1999-2000), and references in “The New Traveller’s Almanac” in book two (2002-2003).

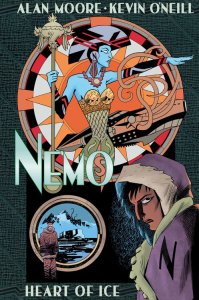

Moore later discussed the Mythos even more directly in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Black Dossier (2007), with its Jeeves and Wooster mashup “What Ho, Gods of the Abyss” and the appearance of Nyarlathotep as an emissary of Yuggoth, and the League graphic novel Nemo Heart of Ice (2013) deals largely with the Elder Thing city in Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness.

Moore’s studies into magic, which are so manifest in some of his works like Promethea (1999-2005), also led him to encounter the Lovecraftian occult. One expression of this encounter is “The Great Old Ones,” a Lovecraftian qabbalah written by Moore and illustrated by John Coulthart, appearing in the collection The Haunter of the Dark and Other Grotesque Visions (1999); another is Moore’s article “Beyond Our Ken,” which appeared in the Midian Mailer 2 (1998) and Kaos 14 (2002), is an appreciation for the occult works of Kenneth Grant. Moore would later go on to weave elements of the Lovecraftian occult into his later creations, including Neonomicon.

Johnson and Burrows adapted “The Courtyard” text as a two-issue limited series black and white comic book: Alan Moore’s The Courtyard (2003), which proved popular enough to be later be collected as a stand-alone slim trade paperback, and the accessory Alan Moore’s The Courtyard Companion (2004), featuring annotations by NG Christakos; both Courtyard and Companion were issued together as a deluxe hardcover in 2004, and a color edition of Courtyard was released in 2009.

Aldo Sax of “The Courtyard” is a caricature of a Lovecraftian protagonist, and by extension of Lovecraft himself: an intelligent white male, effectively asexual, somewhat condescending to others, traits that are manifested in racism and a slight disparagement of homosexuals. Like Lovecraft in New York, Sax is thrust into a low-class milieu of others not like himself, which arouses disgust and disparagement in him, though never vocally. The teenage crowd is explicitly sexual; Johnny Carcosa’s offerings even more so. What the reader gets is not the Mythos regurgitated once again, but an insightful re-imagining of the basic concepts—a nastier narrator describing a grittier world, with the reader left to decide, at the end, how much of the story Sax related was the Aklo talking.

Antony Johnson’s comic script of “The Courtyard” retains the subdued sexual aspects of the prose story, keeping Moore’s distinctive language, which is terrifically effective when combined with Burrows’s wonderfully restrained but detailed artwork (he shows us the cock-ring from Innsmouth with its tiny quills, a glimpse of Pickman’s Necrotica of a human puppet molested by a shadowy, masked figure), and keeping the tone low and realistic to emphasize the transition to a fantastic set of double-page spreads when Sax receives the Aklo later on. Little is lost in the transition from prose story to comic strip, Burrows’s detailed backgrounds filling in for many of Moore’s word-pictures, sneaking in artistic references to the Mythos to complement Moore’s literary ones, some of which are incredibly subtle (as Sax comes down from the Aklo and leaves Johnny Carcosa’s apartment, the narrative shifts in perspective are represented as almost concealed scenes-within-scenes, reflected in windows and picture-frames, even as a couple ruts standing up and fully clothed against a tenement wall).

“Zaman’s Hill” and “Recognition,” the latter of which borrowed from Lovecraft’s biography and the syphilis-induced hallucinations of his father Winfield Scott Lovecraft, were adapted for comics by Antony Johnson with black-and-white art by Juan Jose Ryp and Jacen Burrows. They first appeared in Avatar Press’ three-issue miniseries Alan Moore’s Yuggoth Cultures in 2003.

These two comics adapatations, along with various essays and extras, were packaged as the trade paperback collection Alan Moore’s Yuggoth Cultures and Other Growths (2007), including extensive annotations by NG Christakos.

In 2010, facing a tax debt, Moore took up Avatar Press editor-in-chief William Christensen’s offer to work with them again and wrote a sequel to “The Courtyard,” with art again provided by Jacen Burrows.

Released as a hornbook and four-issue miniseries entitled Neonomicon (2010), the series was later collected with a color edition of The Courtyard (2011).

As with its predecessor, Neonomicon would intimately combine sexuality with its reinterpretation of the Mythos, at once going back to the source material and re-imagining it with more contemporary sensibilities. In Neonomicon Moore subverts, examines, and extrapolates from the tropes he observed in the Lovecraft Mythos, and the literature about Lovecraft and the Mythos that has built up around it.

An important part of this narrative examination and subversion involves unveiling the horrors and secret knowledge that Lovecraft had only hinted at, keeping true to many of Lovecraft’s concepts but with near-exploitative depictions designed to shock, tease, and repel. The orgy of the cultists is not just a pagan revel as suggested “The Call of Cthulhu” or “The Dunwich Horror,” but group sex designed to raise and capture orgone radiation; and the “cosmic rape” of conception and miscegenation with a Deep One is not hidden off the page as in “The Shadow over Innsmouth,” but presented as a brutal, explicitly depiction of rape. As Moore himself put it in an interview with Bram Gieben:

[. . .] actually put back some of the objectionable elements that Lovecraft himself censored, or that people since Lovecraft, who have been writing pastiches, have decided to leave out. Like the racism, the anti-Semitism, the sexism, the sexual phobias that are kind of apparent in all of Lovecraft’s slimy, phallic or vaginal monsters. This is a horror of the physical with Lovecraft—so I wanted to put that stuff back in. And also, where Lovecraft being sexually squeamish, would only talk of ‘certain nameless rituals.’ Or he’d use some euphemism: ‘blasphemous rites.’ It was pretty obvious, given that a lot of his stories detailed the inhuman offspring of these ‘blasphemous rituals’ that sex was probably involved somewhere along the line. But that never used to feature in Lovecraft’s stories, except as a kind of suggested undercurrent. So I thought, let’s put all of the unpleasant racial stuff back in, let’s put sex back in. Let’s come up with some genuinely ‘nameless rituals’ – let’s give them a name. So those were the precepts that it started out from, and I decided to follow wherever the story lead. It is one of the most unpleasant stories I have ever written. It certainly wasn’t intended as my farewell to comics, but that is perhaps how it has ended up. It is one of the blackest, most misanthropic pieces that I’ve ever done. I was in a very, very bad mood. [. . .] I wanted to be unflinching. I thought, if I’m writing a horror story, let’s make it horrible. Let’s make it the kind of stuff that you don’t see in horror stories. Because William Christiansen had, perhaps unwisely, said: ‘Look, you know you can go as far as you want.’ I just got him to repeat that, and said: ‘So… what, I can show erections? Penetration?’ He said: ‘Sure!’ I don’t know if he thought I was going to do it or not but . . . yeah, I did. It’s a way that I haven’t written about sex before. It’s very ugly. [. . .] It reads very well: it’s dark as hell. But it’s kind of compelling. So I went back and read through the scripts for the following three issues, and I thought, ‘Have I gone too far?’ Looking back, yes, maybe I have gone too far—but it’s still a good story. (“Alan Moore: Unearthed and Uncut”)

The road to Providence has been a long path, from those first stories that an impressionable young Moore read to his readings in magic, from the public domain explorations of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to the carte blanche offered by Avatar Press. While it may seem only a short step from “The Courtyard” to Neonomicon, the process of creation has stretched over a decade…and will soon bear fruit once more. Except this time, Moore is moving beyond Lovecraft’s creations, the themes and ideas both boldly proclaimed and subtly hinted at, and grappling with H. P. Lovecraft himself.

Bibliography

“Alan Moore: Unearthed and Uncut” (2010). By Bram E. Gieben. Weaponizer. Retrieved from: http://www.weaponizer.co.uk/onearticle.php?category=nonfic&articleid=181

Baker, Bill and Moore, Alan (2008). Alan Moore On His Work and Career. New York, NY: Rosen Publishing Group.

Comer, Todd A. and Sommers, Joseph Michael (Eds.) (2012). Sexual Ideology in the Works of Alan Moore. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Millidge, Gary Spencer (2011). Alan Moore: Storyteller. Lewes, East Sussex: ILEX.

Mitchell, D. M. (Ed.) (2010). The Starry Wisdom. London, UK: Creation Oneiros.

Tantimedh, Adi and Moore, Alan (2012). “Modernizing Lovecraft: An In-Depth Interview with Alan Moore.” in Bleeding Cool Magazine 1-2. Rantoul, IL: Avatar Press.

An interesting pre comic interview by Alan Moore

LikeLiked by 3 people

Definitely worth a watch… I wonder when Black meets Lovecraft… will it be the last page of issue 12? Handing off the Commonplace Book somehow? A little like Rorschach’s diary ending Watchmen. We’ll see.

LikeLike

This map The Lovecraft Country is quite handy to get your bearings on Robert Black’s travels.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lovecraft_Country

LikeLiked by 2 people

Not really sure where to put this as it’s more of a Road from Providence sort of thing, but Moore’s next big projects is up on Kickstarter, and there’s plenty of Providence related rewards.

LikeLiked by 3 people

New interview with Moore talking about his recent works including Providence.

http://www.comicsbeat.com/alan-moores-secret-qa-cult-exposed-part-i-you-wont-believe-what-they-asked-him

LikeLiked by 1 person

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2016/06/20/peering-into-the-pages-of-providence

Bleeding Cool article.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Don’t know if there are any lovecraftian elements to his new work, but has anyone started in on Moore’s newest book, Jerusalem?

https://www.amazon.com/Jerusalem-Alan-Moore/dp/1631491342

LikeLike

Yup! Alexx and I are working on annotations here: https://alanmoorejerusalem.wordpress.com/ (and there are at least a couple Lovecraft references – “a maze you can’t see” and a quote from HPL’s Fungi from Yuggoth – not to mention parallels with Lovecraft’s groundedness in his region, so a lot of Jerusalem’s walks through Northampton feel a bit like the walks described in Lovecraft’s Charles Dexter Ward, etc.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Providence named one of the year’s best horror comics. It hasn’t wrapped yet, but I’m leaning towards one of the best ever.

https://bigcomicpage.com/2016/10/30/bcp-presents-the-best-horror-comics-of-2016/

LikeLike

Found this shared on FB, but surely a 1970 article by Moore on Lovecraft sure be referenced here somewhere.

http://glycon.livejournal.com/18805.html

LikeLike

Are there pages here on The Courtyard? Seems a bit of an obvious miss if there aren’t.

LikeLike

[…] the biggest and flashiest example. But there’s also The Ballad of Black Tom, Lovecraft Country, Alan Moore’s Providence, the work of Thomas Ligotti, and the books Caitlín R. Kiernan. These are the writers and artists […]

LikeLike

[…] generations of writers and artists. One somewhat infamous project was Alan Moore’s Yuggoth Cultures, a novel of short pieces inspired by Lovecraft’s sonnets. Most of that work was lost, but of […]

LikeLike