Below are annotations for Providence, No. 4 “White Apes” (40 pages plus covers, cover date August 2015 – released September 2, 2015)

Writer: Alan Moore (AM), Artist: Jacen Burrows (JB), based on works of H.P. Lovecraft (HPL)

>Go to Moore Lovecraft annotations index

Note: some of this is obvious, but you never know who’s reading and what their exposure is. If there’s anything we missed or got wrong, let us know in comments.

General: This issue was released 2 September 2015. Issue 4 covers have been publicized via this Bleeding Cool article. Read ourProvidence #4 preview here. We’ve got basic annotations published for the comics pages, with notes on the Commonplace Book soon, and will continue to revise and refine. We strongly suggest reading Lovecraft’s story “The Dunwich Horror” if you want to understand Providence #4 references.

Cover

- The regular cover depicts the Wheatley farmhouse in Athol, Massachusetts, based on the Whateley farmhouse in Dunwich, Mass. as described by Lovecraft in “The Dunwich Horror.”

Page 1

panel 1-4

- The panels on this page are done primarily in reds and yellows, and appears to be a depiction of thermal imaging, as used by some animals, and famously used by the aliens in the Predator film series. Combined with the illegible spoken text, it suggests that the perspective is of a character with very different senses than humans.

- Commenter loopyjoe points out that this may be a workaround for the issue that, logically, invisible eyes could not perceive visible light.

- This page depicts the events, including dialogue, from Page 23 below, but from the point of view of Leticia Wheatley’s invisible monster-like son named John-Divine.

- As noted by commenter, David Car Mar, comparing P1 and P23 the timing of the word balloons is different. The order speakers speak in reversed between the two pages… likely alluding the different perception of time for Lovecraftian creatures (see also mention of time in panel 4 below.)

- Panelwise, the edges of the panels are crisp straight lines, which contrasts with the slightly irregular hand-drawn edges throughout most of Providence (and Neonomicon.) Generally the straight line border has represented a higher level of consciousness – see the dream sequence in Providence #3 beginning on P17 (also Neonomicon #3, P5-9 and #4, P22-23.)

- The four panels (as does P23) form a fixed-camera sequence, which Moore uses frequently, including in Watchmen.

panel 3

- First somewhat clear appearance of Leticia “Letty” Wheatley – for character explanation see P12,p1 below.

panel 4

- The text in the caption box is Black’s barber, who appears on P2.

- “Inbreeding” was a theme in several of Lovecraft’s stories, most notably “The Lurking Fear” and “The Dunwich Horror.” For more on inbreeding in Lovecraft’s fiction, see Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos.

- “Different idea o’ time” actually compares with the different idea of time expressed by Brears and Sax at the end of Neonomicon #4. While the barber appears to be voicing colloquial stereotypes and prejudices, there may be an unknowing grain of truth in what he says.

The barber views a reversed clock (see P3,p2), so this statement contrasts with his profession’s unusual perception of time. (Thanks commenter Moses Horowitz) - “Or behave by decent standards” is another disparagement, but compares to the abandonment of normal social mores exhibited by many of the cultists in Moore and Burrows’ Lovecraftian comics, including the promiscuous orgies of the Dagon cultists in Neonomicon #2 and Providence #3.

Page 2

panel 1

- Black is in a barber shop in Athol, Massachusetts. The reverse letters read “Barber’s Est. 1898” – and his reason for being at the barber is explained on P29; this also establishes that the date for the events of this issue is 4 August 1919.

- As noted in the Commonplace Book (P29 below) the reason the barber is holding a candle near Black’s ear is that he’s applying a singe – an antiquated and now rare hairdressing practice. That this remote barber still practices the outdated singe is a subtle contrast: Athol’s barber is primitive compared to NYC’s, Wheatley is perceived as primitive compared to the Athol barber.

- Commenter Matt Durham points out that in French, the word “singe” means monkey or ape.

- The issue’s title “White Apes” refers to Lovecraft’s short story “Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family“, first published under the title “The White Ape.” It was Lovecraft’s belief that modern humans represented a particular refinement and specialization of the human species, and in line with contemporary studies in eugenics like the Jukes and the Kallikaks, miscegenation between races would result in degeneration as the white “stock” would be lost. His fictions elaborated on this to a fantastic degree, with white-furred “ape-like” creatures featuring in not just “Arthur Jermyn,” but “The Lurking Fear” (caused by incest) and “The Beast in the Cave.” As Lovecraft shared the common misconception that humans had arisen from apes (rather than a common ape-like ancestor), this degeneration often took the form of a “de-evolution” as if man was regressing to an earlier form. This popular misconception was also the source of common racial epithets directed at black peoples (comparing them to monkeys, gorillas, apes, etc. as a way to dehumanize them), who were falsely held by scientific racialists like Ernst Haeckel to be more closely related to apes than other races. Lovecraft’s prejudices were informed and shaped by this scientific racism.

- “No better’n niggers” is Moore’s showing racial prejudice of 1919 white America. The early 20th century was marked as the nadir of race relations in the United States, and the use of ethnic slurs was sadly common and accepted.

- The middle bottle is Bay Rum aftershave.

Page 3

panel 1

- Black confirms that he is in Athol (the real-world inspiration for Lovecraft’s Dunwich) looking for the Wheatley family (Moore’s counterpart to Lovecraft’s Whateley family). Presumably for anyone that missed an issue.

- Commenter Marko Maras points out a possible allusion in the name Wheatley: “In Octavia Butler’s “Wild Seed” (1980), “Wheatley” was the name of the American “seed village” founded by the novel’s antagonist, an immortal body snatcher, for eugenic breeding.”

- Commenter Midnight hobbit reminds us that “Wheatley” is also the surname of well-known British horror writer Dennis Wheatley. See also note to P29.

- “Commenter Sithoid points out that “Tool Town” is an authentic nickname for Athol, which is dominated by precision-tool manufacturing to this day.

- Commenter Nick mentions that “Atholl is a term associated with Antient Freemasonry (after the Dukes of Atholl who were long running Grand Masters).”

panel 2

- “Warlock Wheatley” is analogous to Lovecraft’s “Wizard Whateley”; a warlock is a male witch.

- The clock facing Black is probably a barbershop clock, which has reversed numerals so that the person looking into the mirror can tell the time.

- “Pequoig here on Main” refers to the Pequoig Hotel on Main Street in Athol, now a retirement home. In Providence #3 Commonplace Book (P32) Black mentions that he has checked in to the Pequoig. The Pequoig is shown on P4,p1 below.

panel 3

- “Cass Meadows” is an area in north Athol, long a farming region, going back to pre-Colonial times. It is now a conservation park area. Moore is being meticulous in geography here, so unless it bears especial interest, we’ll forego further.

- “Garland” is Garland Wheatley, first mentioned in Providence #3 P10,p2 and first appears on P7,p4 below.

panel 4

- A “Medicine Man” is sometimes called a lay, faith, or folk healer, usually lacking in formal medical education and preferring natural, herbal, occult, faith-based, and/or atypical methods of curing disease or healing wounds.

Map to Wheatley’s house - The directions given seem to lead to what is now a small dead-end road which is indicated on Google Maps, but obscure enough not to merit a name (though Black identifies it as “the Old Turnpike” on P29). Cass meadows and North Orange Road are clearly marked. The bridge mentioned would be crossing Millers River. “Lower Village Cemetery” appears to now be named “Mt Pleasant Cemetery”. The turnoff to the road which Black takes on P5,p4 is visible on the top of the map at right.

- The striped pole is an ancient and popular marker for a barber’s shop.

- Commenter skeletonpete points out that overall, this barber shop scene draws a contrast between sciences and the occult. Summarizing the excellent comment further: the barber is dismissive of “some medicine man,” though barbers could be seen (historically) as a profession equally ostracized from his station by a hierarchical cabbal. Barbers were once the go to medical dispensers and surgeons. The barber shop was displaced by the surgeon’s theater. Doctors separated themselves via their own guilds and secret societies.

Page 4

panel 1

- The top center 4-story building is the Pequoig Hotel.

- More carts and horses on the street than cars, further suggesting the rural nature of Athol. The little piles in the street are probably horse droppings.

panel 2

- As in earlier issues, flashbacks are shown in sepia tone.

- “Laroy Starrett” is Laroy S. Starrett, founder of the L. S. Starrett Company in Athol, MA. Again, Moore showing his work establishing the realistic setting.

- Black looks a bit tired from his bus ride from Salem.

panel 3

- This appears to be Athol’s Main Street Bridge over the Millers River – compare to contemporary Google street view.

- On the right is a black cat. Black cats have cameos in Providence #3 (P3,p4) and #7 (P25,p4), also three of four Neonomicon issues, and may tie in to Lovecraft’s life and works. See annotations for Neonomicon #1 P17,p4. (Thanks commenter Lalartu)

panel 4

- Another flashback. The dotted speech bubble indicates whispering, which would be appropriate in a public library.

- “Pequoig” (also spelled “Pequoiag”) was the Native American name for the region which became Athol. (Thanks commenter Sithoid.)

- “Arrived later from Salem” is a reference to the exodus from Salem due to the oncoming Witch Trials. The difference between the upstanding and “blighted” branches of the family also derive from the family background given in “The Dunwich Horror“: “The old gentry, representing the two or three armigerous families which came from Salem in 1692, have kept somewhat above the general level of decay; though many branches are sunk into the sordid populace so deeply that only their names remain as a key to the origin they disgrace.”

- Commenter Sithoid points out that Athol

…was indeed founded by 5 families, but that was in 1735. Moore couldn’t’ve possibly make Wheatleys flee from Salem in any other year than 1692, which was the year of the Salem Trials. So it looks like instead he chose to make his version of Athol a century older to allow for a “later” migration from Salem.

Page 5

panel 1

- Another flashback.

- “Bloodlines can degenerate over time. Intellectually, morally….even physically.” is a succinct recap of Lovecraft’s own belief in biological degeneration. Keep in mind that this was set after the idea of heredity had been established but before DNA was discovered.

- “Round-topped hills” is a reference to the hills and mountains described in “The Dunwich Horror“:When a rise in the road brings the mountains in view above the deep woods, the feeling of strange uneasiness is increased. The summits are too rounded and symmetrical to give a sense of comfort and naturalness, and sometimes the sky silhouettes with especial clearness the queer circles of tall stone pillars with which most of them are crowned.

- “Redskins” are Native Americans.

- “Scalpings” was a practice of removing the scalp, or top of the head containing the hair, popularly attributed to Native Americans, though the practice was quickly picked up by the colonists.

panel 2

- Presumably the Lower Village Cemetery mentioned in the barber’s instructions (P3,p4 above) to the Wheatley residence. It appears to be today’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery on Mount Pleasant Street at North Orange Road.

panel 3

- “I think the past gets in the marrow of a place, and maybe of its people likewise” echoes Lovecraft’s deep felt attachment to and identification with the past, as well as to his native city of Providence.

- “it’s nothing to shout about” may be alluding to the line, referred to multiple times in “The Dunwich Horror”: “some day yew folks’ll hear a child o’ Lavinny’s a-callin’ its father’s name on the top o’ Sentinel Hill!“

panel 4

- “The Dunwich Horror” opens with: “When a traveller in north central Massachusetts takes the wrong fork at the junction of the Aylesbury pike just beyond Dean’s Corners he comes upon a lonely and curious country.” This is that fork; see also P3,p4 above, and P25,p4 below.

Page 6

panel 1

- The Wheatley residence, as depicted on the regular cover of the issue; further identified by the name Wheatley on the mailbox.

- The large number of slugs (on mail box and below) and snails (lower-left) emphasize the decay of the property.

- To the left of Black on the porch, the small copper or brass pot is a classical spittoon for disposing of juice and saliva from chewing tobacco.

panel 2

- The device to the left of Black’s elbow is an old mechanical, hand-cranked washing machine.

Page 7

panel 1

- The drain pipe from the roof empties into a rain barrel; possibly the only source of fresh water if the Whateleys lack a well or nearby freshwater stream.

- The door to the shed on the right is visible chained and locked, recalling from “The Dunwich Horror“: “one of the many tool-sheds had been put suddenly in order, clapboarded, and fitted with a stout fresh lock.” The shed contains Leticia Wheatley’s invisible monster-like son.

panel 2

- The shed is visibly the same as from the Women of HPL variant cover for this issue.

- Pools of blood are visible in front of the doors.

panel 3

- It is never quite shown clearly, but it is visible in the upper right corner (and P9,p1), the shed has a gambrel roof, a staple in Lovecraft’s descriptions.

panel 4

- First appearance of Garland Wheatley. Wheatley is Providence’s analog for Old Wizard Whateley from “The Dunwich Horror.”

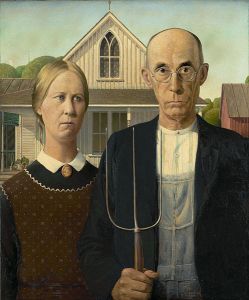

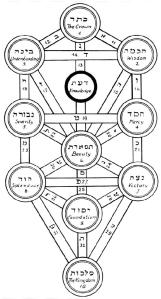

- Wheatley’s constant toting of the pitchfork is reminiscent of the famous painting American Gothic by Grant Wood. It’s also typical in popular depictions of the devil (thanks commenter Daniel Thomas.) It also perhaps resembles the three columns of the tree of life – see P16,p1 (thanks commenter bobsy.)

- Compositionally, Moore and Burrows do interesting things with the pitchfork; here it visibly appears to capture Black.

Page 8

panel 1

- Wheatley is wearing a variety of charms and pins, representing his membership in various organizations. Most of these appear to be distinctly benign: the compass of the Freemasons, the downward-horns and scimitar of the Shriners, an Elks Lodge pin, the triangles of the Knights of Pythias, the double-eagle pin of a 32nd degree mason, etc.

- Commenter Sithoid suggests that what we identified as Elks Lodge pin might be Moose Lodge instead; and that the upside-down star may be a Grand Army of the Republic medal.

- Commenter Nick identifies the upside-down star as the insignia of the Order of the Eastern Star, a group associated with the Freemasons.

- Compositionally, Black’s three upraised fingers sort of hold off Wheatley’s pitchfork.

panel 2

- “Tobit Boggs … Zeke Hillman” is referring to the events of Providence #3.

- “Wall-eyed” has a double meaning. It can mean having afflicted eyes (opposite of cross-eyed.) Walleye is also a type of fish, which would refer to the fish-people Innsmouth look. (Thanks commenters The Gentleman Mummy and Daniel Thomas)

panel 3

- Garland is in his slippers, which with his housecoat suggests he came directly from the house.

- “Salem boys” are Providence #3‘s Boggs and Hillman mentioned above, who reside in Salem, MA.

panel 4

- “Hali’s Booke” is Hali’s Booke of the Wisdom of the Stars (known also by its Latin name Liber Stella Sapiente and its original Arabic name Kitab Al-Hikmah Al-Najmiyya) which is Providence‘s analog for Lovecraft’s Necronomicon. The book is first mentioned in Providence #1 P15,p3, but explored in much more detail in Suydam pamphlet pages at end of Providence #2 P32-40. Generally these annotations refer to this book as the Kitab.

- “1912” is the year that Wilbur Whateley was conceived – on May Eve 1912, according to “The Dunwich Horror.”

Page 9

This page expands on the Wheatley’s break from the Stella Sapiente order, mentioned in Providence #3, P10.

panel 1

- The “society” and the “group called the Stella Sapiente” are the Worshipful Order of the Stella Sapiente, the American coven associated with Liber Stella Sapiente (aka Hali’s Booke or the Kitab – see above panel), Providence’s Necronomicon analog. See Suydam pamphlet pages at end of Providence #2 for extensive background.

- First mention of “Saint Anselm College in Manchester” which is apparently Providence‘s equivalent to Miskatonic University in Arkham. Manchester is the real-life city of Manchester, New Hampshire. There is an actual Saint Anselm College (located directly alongside Manchester, officially in Goffstown, NH.)

Originally, Lovecraft had based Arkham on Salem, Massachusetts, but in Neonomicon Moore had erroneously identified Salem with Innsmouth (see Neonomicon #2 annotations P3,p2), thus, he needed to find a different town as a basis for Arkham within the context of Providence. - “1890” is the year Lovecraft was born.

- In “The Dunwich Horror” the Whateleys also bought cows, which they used to feed Wilbur Whateley’s monstrous twin. Note that these cows appear sickly – with bleeding sores, as in Lovecraft’s story: “the herd that grazed precariously on the steep hillside above the old farmhouse, and they could never find more than ten or twelve anaemic, bloodless-looking specimens. Evidently some blight or distemper, perhaps sprung from the unwholesome pasturage or the diseased fungi and timbers of the filthy barn, caused a heavy mortality amongst the Whateley animals. Odd wounds or sores, having something of the aspect of incisions, seemed to afflict the visible cattle…”

- Analogous to “The Dunwich Horror” the second story of the Wheatleys’ home is being worked on, to contain the Leticia Wheatley’s invisible monster-like son, when it outgrows the shed.

panel 2

- A closer look at Wheatley’s talismans and fraternal society pins. The coin or medallion bears a Cross Potent.

- “When they brung that stone down, ’82” refers to Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space.”

panel 3

- A much-bowdlerized version of the events of “The Colour Out of Space“; in Lovecraft’s story the meteorite was supposed to have been taken away by researchers from the university, where it evaporated. Here, Wheatley suggests that was a polite fiction.

- “On farmin’ land” is one of a handful of places where Moore makes a fairly strong connection between Wheatley and the land he inhabits. Later (P10) he walks Black to the wetlands. When he sees John-Divine is loose he swears by “the Old Land” (P23,p1.) It’s possibly to contrast between the rural Wheatleys and the (presumably) urban Stella Sapiente.

- “Spirits it off to Rhode Island” suggests that the current headquarters of the Stella Sapiente is in Providence, RI, probably making them the reality behind the Starry Wisdom Church from Lovecraft’s “The Haunter of the Dark.”

panels 3-4 (and P10)

- Note the contrast that the natural world is thriving outside of the Wheatley’s property, while inside it things are pretty run-down. Outside the farm gate, bracket fungi (P9,p4 and P10) grow on trees, and P10 shows a full forest canopy, fresh water, dragonflies, frogs, turtle, etc.

This matches Lovecraft’s description from “The Dunwich Horror”: “The trees of the frequent forest belts seem too large, and the wild weeds, brambles, and grasses attain a luxuriance not often found in settled regions. At the same time the planted fields appear singularly few and barren; while the sparsely scattered houses wear a surprisingly uniform aspect of age, squalor, and dilapidation.”

panel 4

- “Old Wade and what’s his name, General Pike’s associate” appears to refer to the same the Wades and the Burens, mentioned in Providence #3 P11,p3, by Boggs who states “the Stell Saps these days, your Wades and your Burens, they’re too high and mighty for us.”

This appears to point to an elitism split in the coven, with presumably educated Wades, Burens, looking down on more working class Wheatleys and Boggs. - It is not clear if the General Pike mentioned is the Revolutionary War commander Zebulon Pike or the Confederate general officer Albert Pike (or another Pike.)

- Commenter Sithoid points out that Albert Pike

…did live in Lovecraftian places (Boston MA, Newburyport etc); but, most importantly, he was a prominent Mason and all but created American masonry (reformed their rituals, expanded the Lodge to all of the US, wrote their code etc). Given that Garland carries an emblem of 32nd or 33rd degree (Pike had the 33rd degree which was supposedly the highest rank), these hints reveal a backstory about close connections between Stella Sapiente and Freemasons of the Scottish Rite.

- As Black alludes to, the “Redeemer prophecy” is in the Kitab. It is mentioned in Providence #2, P39 (Suydam’s pamphlet page [10]) which states “… the book’s [the Kitab] delirious prophetic texts. Inspired by mentions in these of the prophesied ‘Redeemer, by whose byrthe, the great disorder of our worlde shalle once more be above’…” This possibly refers to the events of Neonomicon, and, if that’s right, then the Wheatleys are mistaken.

Page 10

panel 1

- “The Arab’s book” is the Kitab – see P8,p4 above.

panel 2

- “’92 fire” refers to an actual fire that consumed St. Anselm College in 1892.

- “Cunnin’-feller” is a variation on “cunning man,” a term for a type of folk magician in England and the United States; compare with “wise woman.” Cunning men, witches, and other folk magic practitioners were often distinguished from and derided by the more bookish and educated ceremonial magicians.

- “Twenty years we waited for their experiment to work out.” is not entirely clear yet. If the experiment was decided on in 1889 or 1890, that would correspond when the product – presumably Lovecraft, born in 1890 – reached majority at the age of 21 in 1911. Interestingly, this roughly corresponds with the nervous breakdown that prevented Lovecraft from graduating high school.

- “Petty prejudice” is, once again, Moore is casting Lovecraft’s villains in an almost sympathetic light. See also Providence #3 annotations P12,p2 and P20,p1.

- The water body pictured is probably the Tully Brook.

- Note the lushness of the landscape outside the Wheatley farm, contrasting with the desolation inside (see P9,p3-4 above.) We don’t have a definitive interpretation of this scene, but it seems to echo the Wheatley’s connection with the land (see P9,p3) but may also touch on early New England attitudes toward nature. What the contemporary reader sees here is a thriving wetland, though what a 1919 person would see is a festering swamp. Lovecraft’s view of nature is neither horrific nor wholehearted embrace.

Lovecraft often describes wild nature settings in mildly sinister terms, for example, in “The Lurking Fear” there are “ancient lightning-scarred trees seemed unnaturally large and twisted, and the other vegetation unnaturally thick and feverish…” In “The Dunwich Horror” he refers to “stretches of marshland that one instinctively dislikes, and indeed almost fears at evening…” On the other hand, Lovecraft loved walks through the woods and hills, although probably that was a more managed nature than the “real” wilderness. While Lovecraft’s wilderness may add to the fright of a setting, he never really pursued a “horror of the wilderness” compared to Algernon Blackwood’s “The Willows” or anything like that. What Moore and Burrows are doing here is not entirely clear – possibly they are inverting that “instinctive dislike” by portraying the marshland as thriving.

panel 3

- In Black’s “I’d have thought serious philosophers should be above all that” Moore echoes an age-old distinction between mystical efforts to improve an individual spiritually and getting bogged down in mundane pettiness and desires.

- “Distant stars, an eternity’s depths an how man ain’t nothin’” is a bare-bones description of Lovecraft’s cosmic outlook, which focuses on how inconsequential man was in the scheme of the universe, a mere temporary aberration on a cosmic time scale.

Page 11

panel 2

- “Found with all her bones broke like she’d been picked up an’ dropped” is reminiscent of something in August Derleth’s novel The Lurker at the Threshold, a “posthumous collaboration” built around two fragments of text from Lovecraft.

- If Mrs. Wheatley died in 1890, Leticia must have been born before that, making her at least 30 years old in 1919, and probably older.

panel 3

- “Catholic affair” references anti-Catholic sentiment which lingered rather long in the United States. Most of New England’s settlers were primarily Protestant Christians

- “Like the society’s Rhode Island Church” is presumably another (see P9,p3) reference to Lovecraft’s Starry Wisdom Church in Providence, RI (from “The Haunter of the Dark.”) It sounds like the Stella Sapiente have bought or influence over an actual church.

panel 4

Page 12

panel 1

- First clear appearance of Leticia “Letty” Wheatley. Leticia Wheatley is Providence‘s analog for Lavinia Whateley of Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror” where she is described as “a somewhat deformed, unattractive albino woman of thirty-five.”

The lack of pigment marks Leticia Wheatley out as an albino. Albinism is a recessive genetic trait, sometimes associated with inbreeding.

Unlike Lavinia Whateley, who is described as having “crinkly albino hair,” Leticia’s hair is straight; Leticia also lacks the Whateley’s characteristic chinlessness, though she seems to share her father’s high cheek structure. - It may be a slight stretch, but wherever Leticia Wheatley appears, she has some sort of halo behind her head: here a picture frame, next panel the oval table, mostly the picture frame thereafter. Possibly this refers to her being a sort of Virgin Mary. (Thanks commenter Mir Kamran Meyerr)

- “Figurin’ out” would normally imply math, this seems to be closer to sorting out her thoughts, hence the crayons. This is perhaps the first clue that Leticia is either not very intelligent or not altogether right in the head.

panel 2

- “Your story” may refer to Providence as Black’s story.

panel 3

- “But he’s…” is a slip of Leticia’s, presumably thinking of her other child locked in the slaughter shed out back.

- “Willard” is Willard Wheatley, the Providence counterpart to Wilbur Whateley

- “Mrs… uh, Miss Wheatley” – Black not used to dealing with unmarried mothers.

Page 13

panel 1

- “Unless Willard’s off up in the hills again, he’ll most likely be about his studyin’.” – In “The Dunwich Horror,” Wilbur Whateley studied his grandfather’s books of magic and lore and went up among the standing stones on the nearby hills:He ran freely about the fields and hills, and accompanied his mother on all her wanderings. At home he would pore diligently over the queer pictures and charts in his grandfather’s books, while Old Whateley would instruct and catechise him through long, hushed afternoons.

- “Upstairs … renovatin'” refers to how, in “The Dunwich Horror,” old Wizard Whateley repaired the house, and then expanded it to accommodate Wilbur’s growing twin. Unlike in Lovecraft’s story, Wheateley’s house currently lacks a ramp to lead cattle up from the ground floor to the second story.

- Panels 1-4 form a fixed-camera sequence, which Moore uses frequently, including in Watchmen.

panel 2

- The picture on the wall has halos, suggesting a religious scene like the Madonna with child – however, this scene includes two children with halos, foreshadowing Leticia’s twins.

panel 3

- As mentioned above, in “The Dunwich Horror,” at some point the Whateleys moved the growing twin from the locked shed to the upstairs of the house.

panel 4

- “John-Divine” is another slip. With the “Redeemer” prophecy, the Stella Sapiente appear to be melding Hali’s occult prophecies with Christian mythos to some extant. It’s interesting to note that “The Dunwich Horror” (and it’s precursor, Arthur Machen’s “The Great God Pan“) deliberately echo the supernatural conception, birth, and death of Jesus Christ, a thread that has been picked up by Mythos author and religious scholar Robert M. Price, and noted especially by Donald Burleson in his book Lovecraft: Disturbing the Universe.

Page 14

panel 2

- “Oughter” – Archaic or regional term, “ought to” or “should.”

- “People like pictures [in books]” is perhaps Moore giving a nod to the popularity of comics. (Thanks commenter The Gentleman Mummy)

- Panels 2-4 this page and continuing p1-4 the next page all form a a subtle zoom sequence; Moore uses zoom sequences frequently, including on P1 of Watchmen #1.

panel 4

- “Sentinel Elm off Moore Hill Road” is analogous to how, in “The Dunwich Horror,” the supernatural conception took place atop Sentinel Hill. However, there is no Sentinel Hill in Athol, but there is a Sentinel Elm Farm, noted for the Sentinel Elm:

- “My own recollection’s got bits missin’ form it” possibly refers to how, in “The Great God Pan“, Mary’s seeing Pan rendered her an imbecile.

Page 15

This page largely hints that Garland Wheatley was responsible for the impregnation of his daughter in 1912, a view also suggested by some other critics.

Commenter Pete Angelo observes: “On Page 15 panel 4 – the white egg shape in Letty’s eye reminds me of a fertilized embryo attached to the uterus wall – which would be appropriate here since she’s describing conception.” These white egg-shaped highlights are visible for the whole page, and there is one in each eye – suggestive of twins.

panel 1

- “Syringes” used for artificial insemination in cattle was actually relatively new in 1919, so this might be somewhat unlikely but not necessarily anachronistic.

panel 2

- “An the nightjars, they was callin” refer to nightjars, a species of whippoorwills. In Lovecraft’s story, the bird associated with the Whateleys was the whippoorwill, which would supposedly capture the soul at the moment of death. Nightjars are featured prominently in Moore’s comic of the same name, part of which was published in Yuggoth Creatures.

panel 3

- “Daddy is makin’ the angles” likely refers to the hypergeometry of Lovecraft’s “The Dreams in the Witch House.”

- “He was… just big balls, you know?” is a twofold reference: on the one hand, to testicles, and on the other hand to Lovecraft’s description of Yog-Sothoth as “a congeries of iridescent globes” in “The Horror in the Museum“. We will see Moore and Burrows’ interpretation of these globes on the following page.

panel 4

- The close-up zoom into the character’s eye was used earlier by Moore in Miracleman.

Page 16

panel 1

- This depicts a flashback to the event: Garland Wheatley apparently possessed and mating with his daughter.

- The overall color is that of Leticia Wheatley’s eye, showing us that this is her viewpoint.

- The “spheres” hanging above him take the form of a Kabbalistic Tree of Life. The tree of life appeared briefly in Providence #2, in Suydam’s home (P10,p1) and on the cover of his pamphlet “Kabbalah and Faust” (P12,p4.) It’s also prominent throughout much of Moore’s Promethea.

Associating the Tree of Life with Yog-Sothoth (the god-monster-entity who impregnates Lavinia Whateley in “The Dunwich Horror“) has overtones both with “The Dunwich Horror“‘s declaration that “Yog-Sothoth knows the gate. Yog-Sothoth is the gate. Yog-Sothoth is the key and guardian of the gate. Past, present, future, all are one in Yog-Sothoth.” as well as the Kabbalistic magic of Kenneth Grant. - On the left is the Sentinel Elm – see P14,p4 above.

Page 17

panel 1

- “Schoolin’ at mathematics” references the association between magic and mathematics in Lovecraft’s “The Dreams in the Witch House.” So this could be the truth and still jive with young Willard studying sorcery.

panel 2

- “Playmates his own size” foreshadows of Willard Wheatley’s appearance, like Wilbur Whateley in “The Dunwich Horror” who grew at an accelerated rate.

- Garland Wheatley’s pitchfork frames Leticia Wheatley’s face, sort of capturing or threatening her.

Page 18

panel 1

- First appearance of Willard Wheatley, Providence’s analog for Wilbur Whateley in “The Dunwich Horror.” Willard fits Wilbur’s goat-like description: “The strangeness did not reside in what he said, or even in the simple idioms he used; but seemed vaguely linked with his intonation or with the internal organs that produced the spoken sounds. His facial aspect, too, was remarkable for its maturity; for though he shared his mother’s and grandfather’s chinlessness, his firm and precociously shaped nose united with the expression of his large, dark, almost Latin eyes to give him an air of quasi-adulthood and well-nigh preternatural intelligence. He was, however, exceedingly ugly despite his appearance of brilliancy; there being something almost goatish or animalistic about his thick lips, large-pored, yellowish skin, coarse crinkly hair, and oddly elongated ears.”

- As noted by commenter Mir Kamran Meyerr, Willard Wheatley’s hands look inhuman, somewhat reminiscent of tentacles: though he has knuckles, his hands are more fluid than angular, possibly a demonstration of his kinship to the “ropelike” Yog Sothoth.

- The shed recalls a portion of “The Dunwich Horror“: “In the summer of 1927 Wilbur repaired two sheds in the farmyard and began moving his books and effects out to them. […] He was living in one of the sheds.”

- The horseshoe above the door is a common good luck charm.

panel 2

- “Herald-man” is another reference to Black as a sort of herald, as mentioned in Providence #2, P13. Black continues to interpret these mentions as referring to his former work at the New York Herald newspaper.

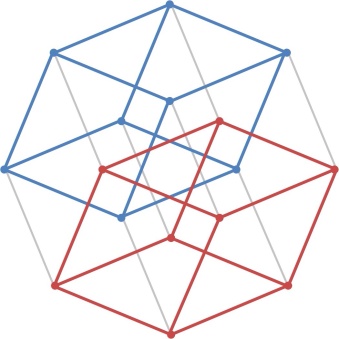

- “Tess’racts” are Tesseracts: a mathematical concept of four-dimensional analogs of cubes. They fit neatly into the implication of “higher dimensions.” The “cubes” that Willard is manipulating are actually the three-dimensional cross-section of the 4th-dimensional tesseracts he’s playing with.

- The map on the wall is labeled “Athol.”

Page 19

panel 1-4

- Throughout this page, Willard is manipulating the clear cubes in ways that would seem to defy the normal laws of physics. The reader can see this, though Black can’t.

- The four panels form a fixed-camera sequence, which Moore uses frequently

panel 2

- “Ahm near six un’ a haff” fits “The Dunwich Horror” timeline. If Willard was conceived May Eve 1912, as Wilbur Whateley was, and born nine months later, that would be the correct age for July 1919. As with Dunwich’s Wilbur, Willard matures at a supernaturally fast rate.

- Willard’s explanation of tesseracts is pithy but essentially correct.

panel 4

- “In the ‘Deemer story” refers to Redeemer Prophecy, mentioned P9,p4 above. Going a bit metafictional now; the Wheatleys are trying to realize the narrative of the Redeemer prophecy from Hali’s book, and the Herald is from a different section or prophecy. However, the details of the Redeemer story don’t fit the events of Neonomicon – but they do fit the events of “The Dunwich Horror” and possibly Lovecraft’s own life – indeed, it would seem that H. P. Lovecraft is the Redeemer experiment of the Stella Sapiente.

While many fans have been speculating that Black will somehow inspire Lovecraft to write his stories, have we got it all wrong? Are the stories already written, in Hali’s book, and the characters acting them out? Moore has played with enough metafictional narratives it’s too soon to tell, but it does make readers wonder at what level this story is being told or should be understood at. - “thuh crazy granpappy, un’ thuh whaht-faced wummun, un’ thuh bad-lookin’ bwoy” – This part of the Redeemer prophecy has clear echoes with both “The Dunwich Horror” and Lovecraft’s own life – after the death of Lovecraft’s father, HPL lived with his grandfather and mother (whose opinion on Lovecraft’s appearance was, in HPL’s own words “devastating”). The parallels between “The Dunwich Horror” and Lovecraft’s family structure have been noted by several critics.

-

Two-dimensional representation of a tesseract. Image via Brian Grimmer Blog The description and depiction of the tesseract matches various depictions available on-line, for example see Brian Grimmer Blog.

- The tesseract does include a Jewish six-pointed star, though this may be coincidental. (Thanks, multiple commenters)

Page 20

panel 1

- “With aor competishun’s whut yu are.” is, again, the suggestion of a division among the various cults – see, for example, P9,p4 above.

- “Put thuh buried places back on top” sounds like a reference to the sunken island of R’lyeh, where Cthulhu sleeps.

panel 2

- “The Aklo lettuhs” is a reference to the Aklo letters, a kind of ancient code-language in the Necronomicon in “The Dunwich Horror” and to a meta-language in The Courtyard and Neonomicon. Lovecraft borrowed the Aklo letters from Arthur Machen’s “The White People.”

panel 3

- “Ah knows who yu is better’n yu do” seems to again refer to Black’s status as some kind of herald (see P18,p2 above.) Other Lovecraftian beings somehow seem well aware of Black, including Zeke Hillman who stated that Black was “the feller all the talk’s about” (Providence #3, P23,p3)

Page 21

panel 3

- A photograph of Willard Wheatley and, presumably his brother – who, like Wilbur Whateley’s brother, is naturally invisible, though you can get an impression of his size from the depression on the couch cushions. The inscription on the bottom is “the Boys 1917.”

- “Ronald Underwood Pitman” appears to be the Providence analog for Lovecraft’s Richard Upton Pickman from “Pickman’s Model” and other stories. Like Pickman, Pitman lives in Boston’s North End. (Nitpicky note: Pickman was actually already mentioned under his Lovecraft-given Pickman name in Moore’s The Courtyard #1 P21,p1. and #2 P9,p2.)

Page 22

panel 2

- “Every month about this time, he takes his nap” is not entirely clear. Monthly cycles are often associated with menstruation, but unless Willard Wheatley is an hermaphrodite, it’s likelier to be some other issue with his hybrid physiology. Commenter Alexx Kay suggests these might have to do with Willard’s prodigious growth.

panel 4

- “Bears Den” is a small cave near Athol, and a detail in “The Dunwich Horror.”

Page 23

panels 1-4

- This scene, from the point of view of John-Divine Wheatley, is shown on P1 above.

- Though we can’t see or hear the invisible child John-Divine, apparently the Wheatleys can. The image of Leticia Wheatley cajoling her child back into the shed, and the Wheatley’s reaction to Willard letting him out, lends resonance with the image of the Women of HPL variant cover for this issue, suggesting Willard might do something to his mother.

This provides a narrative frisson with the opening statement that “Country people, they got a different idea of time” – as the Wheatleys apparently do see things differently than most folks. - As commenter Alexx Kay points out, Black doesn’t seem to notice that the shed contains no equipment for “slaughtering” (as Wheatley states P7,p4 above), but does contain pictures on walls, as if it were a bedroom.

panel 3

- “leave her with it” – As commenter Sithoid points out, in this phrase (repeated in the Commonplace Book on P35), Black consciously interprets “it” as referring to something abstract like “this situation” or perhaps “Letitia’s madness”. In fact, when Garland Wheatley says “it”, he is referring to the invisible John-Divine.

Page 24

panel 1

- “Saint Anselm” – see P9,p1 above.

panel 2

- “Stell Saps” – see P9,p1 above.

- “You’re headed for Manchester” is a bit prophetic. Black is tracking down the Kitab, and that’s where he can find it, but Black didn’t state this to Wheatley earlier.

Page 25

panel 4

- The crossroads reads “Old Turnpike” and “North Orange Road.” This intersection is shown on P5,p4 above. Commenter Sithoid points out that “Old Turnpike” is a parallel construction to “Ancient Track” (see next note).

- “There was no hand to hold me back” – The first two lines of Lovecraft’s poem, “The Ancient Track“, continued on the next page.

Page 26

panels 1-4

- The text boxes for this page are the lines of Lovecraft’s poem “The Ancient Track.”

- These panels form a fixed-camera sequence.

panel 1

- Moore wrote a Lovecraftian short story titled Zaman’s Hill (annotated here) though this was based on another of Lovecraft’s poems, the Fungi from Yuggoth cycle.

Page 27

(Annotations note: Some of the text back matter below refers directly to stuff we’ve already covered in the comics annotations above. In these case, we try not to repeat ourselves, but just briefly refer to the details above.)

Commonplace book

July 30th

- Moore plays a tiny expectations trick in revealing the gender of the brunette. Black mentions “a pretty brunette” (Providence #3, P34) but even though we know Black is homosexual, it is easy to assume he is describing a female. Not until this issue is it revealed that the brunette is a gay male. As in Providence #1, Black is so closeted that even in this Commonplace Book diary, he doesn’t let the reader know what gender his lovers are.

- Marblehead: an American Undertow echoes Richard Lupoff’s novel Marblehead, originally published as Lovecraft’s Book. The novel is a fictional episode involving Lovecraft becoming involved with an American national socialist movement tied to Nazi Germany. (Marblehead, MA is a real life town, Lovecraft based his fictional Kingsport on. Marblehead was mentioned a few times in Providence #3, beginning P9,p1.)

- Garland Wheatley – see P7,p4 above.

- Mr. [Tobit] Boggs of Salem – see Providence #3 P7,p4.

- “Wilde” is Oscar Wilde, famous Irish fantasist and homosexual.

- The World Turtle mytheme is most prevalent among the native peoples of North America, and formed the foundation for the popular Discworld series by the late Terry Pratchett. To a small extent it prefigures a Lovecraftian mythos: humans as insignificant, at the whims of larger entities.

August 2nd

- “Poe” is Edgar Allan Poe, famous American short story writer, and one of Lovecraft’s chief inspirations. Much of the form of Lovecraft’s fiction owes itself as much to Poe’s early detective stories as much for his weird and gruesome tales.

- “This story would involve a young investigator…” is Moore basically capturing in a nutshell the trope of the occult investigation that Lovecraft, though he did not originate it, helped to popularize and which forms the basis for innumerable pastiches, and of course, could well serve as the basis for the plot of Providence itself.

- Commenter le110pillole points out that “a young journalist […] led by stages through a series of minor weird incidents until finally he encounters the supreme catastrophic nightmare” is describing Black’s own life within Providence.

- “Tom Malone” – see Providence #2, P2.

Page 28

Commonplace book

August 2nd continued

- “Epistolary form” is a story or novel that is told in the form of a collection of documents, usually letters (epistles), but also diary entries, statements, newspaper accounts, etc. rather than a direct narrative. Lovecraft used found documents, letters, and other such literary mechanisms in his own fiction for a number of purposes, ranging from exposition to framing devices. The most notorious example is “The Diary of Alonzo Typer.”

Commenter oddforum points out that with the Commonplace Book and other back matter, Providence is being told partially in epistolary form. - “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” is, of course, Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula, which is the epitome of the epistolary form.

- “I think it’s important to make one’s more fantastic stories as believable as possible” again echoes some of Lovecraft’s thoughts on the matter, as expressed in his Notes on Writing Weird Fiction.

- Commenter le110pillole points out that, again, the “tendency not to believe that anything out of the ordinary is going on, even if evidence is mounting to the contrary” describes Black himself.

Page 29

Commonplace book

August 3rd

- “Share his miraculous abilities and longevity” in some ways echoes the cannibalism and associated longevity of “The Picture in the House,” suggested last issue.

- Black’s interest in looking great for the brunette explains why was in the barbershop (P2-3 above), and sets the date for the events of the issue.

August 4th

- “I’ve had a devil of a time persuading Athol’s citizens to tell me anything about [the Wheatleys]” (emphasis added) – Commenter Midnight hobbit suggests that this may be a subtle reference to British horror writer Dennis Wheatley, best known for his novel The Devil Rides Out.

- North Orange Road is an actual street in Athol. The “Old Turnpike” may or may not be. See P3,p4 above. Commenter Sithoid points out that there is an “Old Turnpike Rd” a few miles from Athol. Commenter Chris Coleman suggests:

Old Turnpike Rd probably refers to the Fifth Mass Turnpike (Leominster to Greenfield going through Athol). These turnpikes were pay roads set up in Massachusetts from the very late 18th to the early 19th centuries. Many parts of this road have been either incorporated into now relatively major routes, or sometimes allowed to be overgrown with brush. Small pieces of this road do still exist, but very little still denote its historical significance

- Cass Meadow – see P3,p3 above.

Page 30

Commonplace book

August 4th continued

- Garland Wheatley’s appearing like a goat, is reminiscent of descriptions of his grandson (and possibly son) Wilbur, in “The Dunwich Horror.”

- “Knights of Pythias” is a fraternal and secret society.

- “Hali’s Book” – see P8,p4 above. (Generally call the Kitab in these annotations.)

- “Stella Sapiente” – see p9,p1 above.

- “Bringing down the stone… 1882” refers to the events of “The Colour out of Space.”

- “Redeemer prophecy” – see P9,p4 above.

- “Daughter Leticia [Wheatley] – see P12,p1 above.

Page 31

Leticia Wheatley’s first drawing

- A childlike rendering of the scene shown on P16 above, showing Leticia Wheatley (marked with red eyes due to her albinism), Garland Wheatley, the Sentinel Elm, and the connected spheres of Yog-Sothoth/the Tree of Life.

- Additional detail from commenter Ross: Leticia’s drawing of Willard’s conception has the various colored spheres of the Tree of Life/Yog-Sothoth. The violet or purplish one likely represents Da’ath, the sphere of the Abyss, which in Moore’s Promethea, was shown as a gateway through which various lovecraftian creatures entered our cosmos. There’s mention of HPL in that issue, and a cabal of occultists called the Blacks Brothers.

Page 32

Leticia Wheatley’s second drawing

- A rendering of “John Devine,” (called “John-Divine”) Leticia’s other son, who is invisible to the reader (see P1 and P23.) The overlapping features of the creature – including the black outline of old Garland Wheatley’s face – correspond with the description given in “The Dunwich Horror“: “It was a octopus, centipede, spider kind o’ thing, but they was a haff-shaped man’s face on top of it, an’ it looked like Wizard Whateley’s, only it was yards an’ yards acrost. . . .”

- The overlapping aspect of the drawing may represent the creature’s multi-dimensional nature, where only certain parts of it are visible at a time.

Page 33

Commonplace book

August 4th continued

- “Poor fellows coming back from Europe at the end of last year” refers to World War I. Moore is perhaps suggesting that Leticia Wheatley’s slow-witted-ness is post-traumatic stress.

- “Sentinel Elm” – see P13,p4 above.

- “These things going on among the rural poor” refers to incest, and generally interbreeding.

- “The ultimate monstrosity” has a double meaning: incest, and Yog Sothoth (see P15-16 above.)

- Willard Wheatley – see P18,p1 above.

- “Goat-like look” echoes descriptions of Wilbur Whateley in “The Dunwich Horror.”

- “He said he was sixteen and a half” is Black’s mistaken hearing of Willard Wheatley saying he is six and a half – see P19,p2. His Lovecraft analog Wilbur Whateley matures abnormally fast in “The Dunwich Horror.”

- “I remember a big pot of glue there” is wrong – see P18-21. Not for the first time, Black is remembering incorrectly.

Page 34

Commonplace book

August 4th continued

- “[Willard Wheatley’s tesseract] gave me a mild headache” is a reference to Black not being able to perceive a fourth-dimensional object.

- To “gawp” is to stare rudely.

- “[Willard Wheatley] had something wrong with both legs” refers to Wilbur Whateley (in “The Dunwich Horror“) whose legs “roughly resembled the hind legs of prehistoric earth’s giant saurians; and terminated in ridgy-veined pads that were neither hooves nor claws.”

- “The caption underneath the picture had a misprint… ‘the boys’ instead of just ‘the boy’…” is Black misinterpreting the photo (P21,p3 above) of Willard and his invisible brother John-Divine.

- “Ronald Pittman” – see P21,p3 above.

Page 35

Commonplace book

August 4th continued

- “The Pequoig [Hotel] – see P3,p2 above.

August 5th

August 12th

August 13th

- “That they thought…” is Brown avoiding using a gendered pronoun, to avoid admitting his homosexuality.

- “Chatterton” is Thomas Chatterton, then a famous British poet.

Page 36

August 13th continued

- Milwaukee, WI, is Black’s hometown – see Providence #1, P6.

- The sea-narrative has some obvious overtones with growing up homosexual (“had been made to feel unnatural and unworthy simply because of his human nature”), and echoes some of the homosexual interpretations of “The Shadow over Innsmouth.”

- “Eugene O’Neill” is an American realist playwright. Commenter Sithoid elaborates:

I believe Robert specifically refers to “Beyond the Horizon” (published in 1918, staged in 1920) which features a rural youngster dreaming about the sea. There are (probably) no homosexual overtones in that play, as O’Neill was, most likely, heterosexual; these are Robert’s own input into this concept, as he himself states.

Page 37

August 13th continued

- “I was starting to get quite excited about all the shipboard material” is possibly a veiled reference to the prevalence of situational homosexuality aboard maritime vessels, an occupation almost exclusive to men.

- “Badge of shame” references The Scarlet Letter, mentioned in the next sentence.

- Black was reading “Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter” in Providence #3, P16,p2.

August 14th

Page 38

August 14th continued

- “Gustav Moreau” was a French symbolist painter; several of his most memorable feature fantastic monsters. Commenter Mr F notes that Moreau appears in Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, vol 2.

- “Hieronymus Bosch” is a Medieval Dutch painter, also noted for his fantastic monsters. Moore references Bosch in his Splash Brannigan story in Tomorrow Stories #7.

- A “chimera” is a creature made of disparate parts, the word taken from the chimera of Greek myth.

- “Perhaps the occasional vampire or were-wolf” – Lovecraft’s horror fiction was exceptional in part because it eschewed traditional monsters and familiar horrors in favor of breaking new ground.

- “Verne or even a Wells” – Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, early science fiction writers.

- “Well’s Martians” – Referring to The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, where Martians invade the Earth.

- “Bierce” – Ambrose Bierce, American writer, see annotations in Providence #1.

Page 39

August 14th continued

- “Richard Marsh’s more popular The Beetle” – The Beetle was a supernatural horror novel released at the same time as Bram Stoker’s Dracula, written by Richard Marsh (pseudonym of Richard Bernard Heldmann). The Beetle has a cameo in Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, volume 2 (thanks commenter Ross.)

- Commenter Sithoid points out:

“Leticia’s phantasmagorical insectile hybrid” and “for her to have conceived grotesques” (and possibly other instances in earlier entries): unknowingly for Robert, his wording hints at Leticia being the mother of that creature rather than an artist.

- “…with nary a witch or a warlock anywhere in sight” is ironic, concerning that Black has spent most of this issue conversing with a warlock (identified as such on P3,p2-3). Commenter Sithoid suggests that the phrase “may also refer to The Stella Sapiente whom Robert is yet to meet, or to John Divine whom he was unable to see.”

August 17th

- Prissy Turner and Sous le Monde featured back in Providence #1.

Page 40

August 17th continued

- “Miss Dingbat” – A bit of a derisive nickname for his erstwhile lover, “dingbat” is a colloquial idiom for someone silly.

August 19th

- “Dr. North” – A possible analogue to Dr. Herbert West of Lovecraft’s “Herbert West—Reanimator.”

Back Cover

- This letter is quoted from Lord of a Visible World 239, a sort of autobiography of Lovecraft pieced together from his correspondence.

- “Munn” – H. Warner Munn, a fellow pulpster and correspondent of Lovecraft.

- “Cook” – W. Paul Cook, an amateur journalist and publisher, friend of Lovecraft.

- “Bear’s Den” – The aforementioned landmark which Lovecraft incorporated into his fictional Dunwich region.

- “Lillian D. Clark” – One of Lovecraft’s aunts.

>Go to Moore Lovecraft Annotations Index

>Go to Providence #5

With Wilbur Whateley on the portrait cover and Lavinia on Women of HPL there is a great possibility this is the Whateley house. It resembles the house in the film of the same name as Lovecraft’s work. The moon is also shown behind it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks – makes sense – we just haven’t gotten to it yet!

LikeLike

Can anyone submit a photo/capture of the house from the 1970 film? I tooled around on YouTube and didn’t see it.

LikeLike

Here’s a capture of the DW house from the movie – though there are some similarities, it doesn’t look similar enough for me to include in the annotation.

http://s21.photobucket.com/user/spacemonkey_fg/media/Dunwich3.jpg.html

LikeLike

The house may not look like the one in the film, but they do have similarities. Alan Moore is not going to depict his version exactly to the one in the film, but he definitely drew inspiration from it, which is why I mentioned the moon.

Here’s a pic of the moon from the film as the Whateley house is engulfed in flames:

http://s1318.photobucket.com/user/2dopesymbiote/media/Mobile%20Uploads/Untitled_zpsqqylw4zx.png.html?sort=3&o=0

LikeLike

“the dunwich horror” is probably my single favourite lovecraft story… i am having quite a hard time keeping my anticipation for this instalment under control..!

LikeLike

Hate to do this… BUT I got issue 4 in the mail a few days ago (gloat gloat- sorry!). I pre-ordered it from Avatar. Now, I also pre-ordered issue 3 which came to me LATER than the in store date! This one came

sooner. Go figure. Anyway it’s not going to let Dunwich fans down, I gua-ron-tee! No spoilers. But it’s awesome.

LikeLike

I just picked it up, and I agree. Great stuff. It’s also the most novel interpretation of Yog-Sothoth I’ve seen to date.

LikeLike

Don’t want to spoil anything for anybody so I’ll lay low- other than saying again it’s a dynamite issue. Alan Moore’s take on all this stuff is so fresh and brilliant.

LikeLike

On page 20: panel 3, the Star of David can clearly be seen in the center of Willard Wheatley’s finished tesseract.

LikeLike

Garland Wheatley’s ubiquitous pitchfork is also reminiscent of the trident often seen in pop representations of the devil.

LikeLike

You’ll also notice it’s used as a framing device in one part, around Leticia’s head – probably implying punishment for her if Garland finds out she spoke out of turn, or even foreshadowing her eventual death.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t notice that but I will definitely check it out. Thanks!

LikeLike

The fork also looks like Yog-Soth, to Leticia’s eyes.

LikeLike

i saw the fork – i think *she* sees the fork – as a reminder of the way he abused his power to get her knocked up by the elder forces in the first place. sure, she told they “we will show them”, but he never told her WHAT he was planning to do, did he? and if he was like a cosmic syringe, then what did that make her, anyway – ?

see, apparently out in the country that’s what you do… run them inot the barn and then use a big fork to opin them uo against a hay bale… easy enough after that. and how the hell would i know this??? erm, fair question… let’s see, actually from robert nye’s *faust* among other things…

LikeLike

jeez, soz about not proofing that before sending – !

“sure, she told they” – shd read “sure, he told her”

(the ones in the second para are easy enough to comprehend i think!)

LikeLike

Surprised you didn’t note how Leticia’s talk of people needing pictures in books is a quiet nod to Moore’s own faith in the superiority of the graphic novel as a medium over prose.

LikeLike

well, i’m not sure about that. AM is also a prose writer, after all – to put it mildly. i think it’s more just letty acknowledging quietly that she struggles with reading and writing; and also – like other trauma victims – she finds it easier to communicate and work out what has happened to her through pictorial imagery rather than words. moore is just telling us how profoundly damaged she is imo

LikeLike

You’ll find the entry in the commonplace book for August 2nd not only describes the framing device for many of Lovecraft’s stories – “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” and “The Horror At Red Hook”, for instance – but is also, in an unpleasantly sinister way, an eerie description of the story so far. How terrible for the protagonist when not only does he not know he’s in a mystery story, he doesn’t even realise that fact when he describes it to himself in his notebook…

LikeLike

The last line in the book refers to a “Doctor North”… does this mean Black is going to meet Herbert West’s counterpart next issue?

LikeLike

Based on one of the alternate covers for the next issue, I tend to think he’s headed towards Manchester (apparently the real-life stand-in for Arkham), where he’ll encounter the events that inspired “The Dreams in the Witch-House.”

LikeLike

i wonder what “Keziah” has behind her back? : )

LikeLike

In “Arkham” he could meet Herbert West AND Keziah Mason. I mean Doctor North and K. Massey of course.

LikeLike

The Whateley Boy’s story about “The ‘Deemer Prophecy” might somehow fit, based on how he describes it – the “Crazy Granpappy” could refer to the Deep One that serves as the father (in that it is a primeval being with an unfathomable mind), Brears is pale and sombre and even wears whiteish makeup, and so could be the “White-Faced Woman”, and of course any Cthulhu born into this world would fit the description of a “Bad-Lookin’ Boy”.

LikeLike

I think the three he refers to are his Grandpa, mom and him. The story being of course Dunwich.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What I mean is he’s referring to a generic prophecy, which could be filled by him and his but could also be filled by the people I mentioned above – as he says, the Wheatley family has competition.

Perhaps he was hoping John-Divine would eat Rob Black, preventing his book from being published and somehow upsetting the chain of events leading to Neonomicon – and thus leaving the path clear for him and John-Divine to be the ‘redeemers’.

LikeLike

clever spot!

LikeLike

In the commonplace book entry, Black mentions Richard Marsh’s The Beetle (1897) a superb horror novel admired by both Lovecraft and Moore, which was adapted for the screen in 1919 by British director Alexander Butler, the film is since lost, much to the consternation of cinephiles. The shape-shifting character has a cameo of sorts in The League of Extraordinery Gentlemen vol. two.

LikeLike

LikeLike

Our protagonist, I fear, is a pretty poor reporter. He misinterprets things going on right in front of him. For example, on page 33 in the Commonplace book entries, Black states that Willard is almost 16 and a half, when on page 19 Willard says, “Ahm near on six un’ a haff.” Black apparently misheard that as “I’m near one-six and a half.” He also misremembers Willard using glue to assemble the tesseract, when Willard very clearly is not. As Black himself unwittingly highlights on page 28, we’re left to wonder how long Black can keep misinterpreting plainly-supernatural events going on right in front of him before he realizes the truth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with this observation by Padraig. It almost seems Moore is portraying Robert Black as a Goodman Beaver type character in this series.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I wondered if John Divine was a word play on “join the divide”, touched upon in the original story.

LikeLike

More likely either St John The Divine, the nutcase who apparently authored the Book Of Revelations in the Bible, or perhaps just John being a common name for a man, and he’s somehow divine, in a Lovecraftian way.

Did HPL write much about Willard’s invisible brother? He’s not entirely a Moore creation, is he?

LikeLike

The invisible brother basically IS The Dunwich Horror. Not Moore’s creation but Lovecraft’s

LikeLiked by 1 person

When reading Moore, when you find yourself asking what “the meaning” of an oddly put-together name, word, or phrase, most often the answer is “all of the above”.

LikeLike

Page 14: Framing of painting/image behind the head of Leticia Wheatley is reminiscent of halos painted behind the head of Mary in medieval/renaissance paintings. This echoes the contents of the “Madonna with Twins”-type painting behind Leticia.

Page 18: Willard Wheatley’s fingers are drawn to appear almost tentacle-like. Though he has knuckles, his hands are more fluid than angular. Possibly a demonstration of his kinship to the “ropelike” Yog Sothoth.

Page 20: This may have been mentioned already; the tesseract forms a Star of David.

Page 20: Willard’s hat and shoes tend to suggest that he may possess horns and hooves, particularly in light of the possible allusion to horns (via pitchfork) on Page 17, Panel 1.

LikeLike

You could also see the one glowing ball behind Wheatley Sr.’s head during the, ah, copulation scene as a halo.

LikeLike

Glad I read all through before posting the following thought (already noticed when i was reading the comic): the structure above his head being the Tree of Life, he is ‘halo’ed by the sephiroth MALKUTH, which unites the material world to the spiritual, higher, say, Godly order.

That is what this incestuous union effected.

LikeLike

Perhaps the Bay Rum on the second page is a small interconnection with the Rum-Run of last issue?

LikeLike

Bay Rum, despite the name, largely skirted Prohibition by including additives (to make it a patent medicine) or specifying for external use only.

LikeLike

On page 8: panel 2, Garland Wheatley derisively refers to Zeke Hillman as “that wall-eyed bastard”. A walleye is a fresh water fish that can be found in Canada and some northern regions of the United States.

LikeLike

True, but it may also be a double meaning; “wall-eyed” is an attribute considered the opposite of “cross-eyed”, where one’s eyes typically face in different directions while resting (like a fish) rather than coordinating together.

LikeLike

Note above that Oscar Wilde was Irish rather than British.

LikeLike

Good catch, I’ll fix that.

LikeLike

At the time of Oscar’s birth, and through his life, Ireland was British property. So Oscar was British.

LikeLike

cf. issue #8: “Is that a British accent?” “That rather depends whom you ask.”

LikeLike

Page 31.

Leticia’s drawing of Willard’s conception has the various colored spheres of the Tree of Life/Yog-Sothoth. The violet or purplish one likely represents Da’ath, the sphere of the Abyss, which in Moore’s Promethea, was shown as a gateway through which various lovecraftian creatures entered our cosmos. There’s mention of HPL in that issue, and a cabal of occultists called the Blacks Brothers.

LikeLike

>“like the society’s Rhode Island Church” – Presumably another reference to Lovecraft’s Starry Wisdom Church in Providence; here it sounds like the Stella Sapiente have bought or influence over an atcual church.

First off, you’ll want to correct “atcual”, which I suppose you mean “actual”.

More importantly, I’d say that the Stella Sapiente is the Starry Wisdom church, as Stella Sapiente is Latin for Starry Wisdom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m quite sure it is noted in the story that Stella Sapiente is Starry Wisdom…

LikeLike

..!

managed to miss the launch date for this in the end- just got my hands on a copy today though. ahhhh…!

so much is *left unseen* – just enough is glimpsed. this is powerful stuff {{{@}}}

(*lost girls* is very good on the subject of incest of course…)

one wonders whether john-divine will be seen at some point though..! (perhaps in the next dream sequence)

gonna go ‘way an’ ponder on this’n, some….

LikeLike

I agree the whole “This story would involve a young investigator…” part from pages 27 and 28 did seem like Moore was having Black unwittingly sum up his own story- in fact it seemed a bit too on the nose for me in terms of predicting that Black will be dead by the story’s end.

But I guess Black’s discussion of how the protagonist doesn’t realise they are in a mystery story means that he also doesn’t see that he’s unwittingly describing his own journey- from the epistolary form (which explains now why Providence has these Commonplace Book entries in each issue- they’re necessary for story itself to exist after Black’s demise), to the fact that the protagonist would think they it was a ‘trick of the light’ or they were ‘hallucinating’ if they saw something so out of the ordinary (a process of self-deception Black has already been through after the events in Suydam’s cellar- putting it down to a nightmare)- and how the protagonist will have severed ties with his previous life- just as Black himself as done.

I hope I’m wrong but it does feel like Moore was almost having a little chuckle here as he had Black sketch out his own journey and tragic end without realising it.

LikeLike

Your comparison of the Redeemer prophecy with Lovecraft’s own life is intriguing, considering Black’s note at the end of Aug 16 that the Wheatleys’ everyday life is horror enough already.

Also makes me think of the protracted arc in “Atomic Robo” where it was revealed that Lovecraft himself was possessed all along by a nameless thing from beyond time, though not one he wrote about.

LikeLike

Might “Well’s Martians” be a veiled reference to the meteorite from “Colour Out of Space” — if I recall correctly, it either fell in the well or poisoned the well water.

Great annotations, by the way. Thanks for sharing it all, much appreciated.

LikeLike

p35 – NB chatterton was specifically a forger – and his fame/remown/importance is very much tied to that. he wrote several “shakespeares” which got the academics at the time quite hot under the collar until they were exposed as fakes – the guy was not just a poet, for sure!

LikeLike

Intended or not, Black’s barber shoppe session offers an interesting aside to the overall theme of the series; the thin line of perception between old sciences and occultism.

Although dismissive of “Warlock Wheatley” viewing himself as “some medicine man,” the barber could be seen (historically) as a character equally ostracized from his station by a hierarchical cabbal.

Barbers were once the go to medical dispensers and surgeons. The barber poll itself is a throwback/analog to the display of blood and bandages that once noted an establishment offered surgical services. The bay-rum is a good catch as a vestige of the profession’s previous incarnation as a medicinal outlet.

The barber shoppe was ultimately displaced by the surgeon’s theater. “Doctors” separated themselves via their own guilds and secret societies, but read the description of the surgical chair in Machen’s opening chapter of “The Great God Pan”, and you’d expect to get a trim, or a “singe,” along with the experimental neurological procedure.

LikeLiked by 2 people

5.1: The reference to scalping may be intended to ironically compare with the barber’s singing a few pages earlier.

12.3: Is the name Willard deliberately evoking the 1971 horror film (or its 2003 remake) about a boy whose only friends are rats? (A tale which is itself a bit reminiscent of HPL’s “The Rats in the Walls”.)

18.2: I don’t think the cubes represent “three-dimensional cross-section of the 4th-dimensional tesseracts”. Given that there are exactly eight of them, I believe they are meant to be the “sides” of a single disassembled tesseract that WIllard reassembles over the course of the scene.

22.2: Given how large he is for a six-year-old, I would expect these naps to accommodate growth spurts (and the associated “growing pains”).

23.1: An attentive reader will note (though Black does not) that the shed contains no equipment for “slaughtering”, but *does* contain many pictures on walls, as if it were a bedroom.

27-28: As other have noted, Black is certainly describing his own story here. What I think others have mostly missed so far is that Moore is using Black’s Commonplace Book (in part) to describe his *own* process *as a writer* in composing this story.

32: See also Moore’s description of a magical ritual, during an extended interview with Dave Sim:

“…I found myself seemingly in conversation with an entity that identified itself as “One of the Nine Dukes,” and then upon closer interrogation as “Asmoday.” Its “body,” when I asked it to show me what it looked like, consisted of a shifting and shimmering latticework of repeated spider motifs, all identical but at different scales. These, while keeping their colouring consistent, appeared to be constantly turning themselves inside out through a spatial dimension that was foreign to me, becoming on the reverse a similar shifting lattice, this time with a reiterated lizard motif. This would turn itself inside out and become the mesh of spiders again, and so on. As a constant background to this effect, there was a beautiful pattern composed of peackock’s-tail eyes. The entire thing was like a 360-degree sphere or field of presence that surrounded my head, moving and speaking lucidly to me (and with great politeness and charm, it must be said).”

LikeLiked by 3 people

I wanted to comment what you said in 27-28: Moore is explaining what will happen in the story but also his own technique.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s a pic Moore drew of said encounter:

LikeLike

Oh wow that was a crazy bad html attempt. here it is:

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks again for all the great work. A quick question: in my digital copy of Providence #4 the Commonplace Book part ends abruptly in the middle of a sentence. As this fact have not been adressed yet (bur perhaps i have miised something) I was wondering if it was on purpose or if my copy is somehow incomplete.

LikeLike

Commonplace Book ends mid-sentence: “… Dr. North’s rooms here in Manchester and”

LikeLike

Thanks Joe

LikeLike

Hi everyone

2 quick thoughts.

– Pages 1/ 23

On each panel, word balloons are on an exactly inverted reading order ( This could be another analogy of “time passing differently”, but this time for the “paranormal” creatures).

– On the commonplace book ( forgot the page) Black mentions that he is SURE he saw some glue on Willard’s table, which of course there wasn’t. It’s his mind filling in the gaps for things paranormal, once again a parallelism for the story described on pages 27 and 28.

Keep up the good work! Regards!

LikeLike

Not sure if anyone’s posted this link yet but it’s definitely worth a look!

LikeLiked by 2 people

thanks !

LikeLike

I understand Moore is talking quite freely there, but I think it’s important to note that although Lovecraft’s personal bigotries may have been similar to those of his wider contemporaries in character, they were not in tone or scale. Lovecraft was excessively fucking racist and remarkably bigoted even for a man of the time, as this important essay shows (content note: massive racism)

http://mediadiversified.org/2014/05/24/the-n-word-through-the-ages-the-madness-of-hp-lovecraft/

Meant to post this ages ago, but me and a couple of idiots chatted about Providence 4 for a bit on this podcast here – the Prov chat starts from about 26 or 27 minutes in

http://mindlessones.com/2015/09/07/silence-155/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed that podcast! Let us know about future episodes!

LikeLike

>Wheatley’s constant toting of the pitchfork is reminiscent of the famous painting American Gothic by Grant Wood. It’s also typical in popular depictions of the devil (thanks commenter Daniel Thomas.)

True, but he’s WIZARD Wheatey, yes? The bathrobe is his robe, and the pitchfork is his staff, both signs of his office, and in the case of the pitchfork possibly needed to conduct certain magical actions.

LikeLike

I must also say how funny it was to have the barber comment about the Wheatleys having a “different sense of time”, given his use of a backwards barbershop clock. The barber is always seeing time differently!

LikeLike

Once again Black is using “their” instead of “his” when talking about a male lover in the Commonplace Book. As this time it is not possible to explain this by referring to a dual personality (Lillian/Jonathan), it appears that DCo was correct (in the comments on issue 1) in assuming he is doing this in order to hide the gender of his lover(s). Also when a man talks about a “brunette”, the first reaction would be to think that he is talking about a woman.

LikeLike

We agree (and to our credit we did mention most of that – see P27 July 30 notes)

LikeLike

I missed that, sorry.

Just wondering if his attitude here could indicate (as others have suggested I think) that Black is hiding other things in the Commenplace Book. Can anyone be so naive? Are his motives for looking for Hali’s Book really so innocent?

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a non-native English speaker, I’d like to know if this is more or less a “common” way of avoiding the gender or if it sounds as forced as it sounds to me (they/their being plural).

Or was this some “slang” trick to avoid refering to the gender of transsexuals and/or transvestites back then? Or a rare “invention” of Moore?

LikeLike

Not sure how it would have sounded in 1919, but it’s a somewhat common way of writing gender-neutral language today. Not a rare invention.

LikeLiked by 1 person

While it would not be considered rare in 2015, in 1919, the whole idea of using gender-neutral language was nowhere near the mainstream. I don’t know if it was common in use *by* gay people back then, but it certainly wasn’t used in common discourse.

LikeLike

Alexkay I think you’re wrong about that; taking a look on the Wikipedia article for “Singular they” brings up a list of very old examples in English writing (copied below). “They” as a singular gender-neutral pronoun does not necessarily have any gender/political connotation in English:

——————————————–

“If a person is born of a . . . gloomy temper . . . they cannot help it.”— Chesterfield, Letter to his son (1759);[17] quoted in Fowler’s.[18]

“Now nobody does anything well that they cannot help doing”— Ruskin, The Crown of Wild Olive (1866);[19] quoted in Fowler’s.[18]

“Nobody in their senses would give sixpence on the strength of a promissory note of the kind.”— Bagehot, The Liberal Magazine (1910);[20] quoted in Fowler’s.[21]

Alongside they, however, it was also acceptable to use the pronoun he as a (purportedly) gender-neutral pronoun,[22] as in the following:

“Suppose the life and fortune of every one of us would depend on his winning or losing a game of chess.”— Thomas Huxley, A Liberal Education (1868);[23] quoted by Baskervill.[24]

“If any one did not know it, it was his own fault.”— George Washington Cable, Old Creole Days (1879);[25] quoted by Baskervill.[24]

“No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.”— Article 15, Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948).[26]

In Thackeray’s writings, we find both